Guide to Buying Fibreglass vs Aluminium Boats

Friday, 03 October 2025

Words and images by John “Bear” Willis

Once upon a time, I owned a 5-metre Quintrex Fishmaster aluminium boat and thought it was the best boat ever made – that was until I took up game fishing. Sure, it was a great all-rounder, but it was certainly not that mythical “Perfect Boat”. Nowadays, I believe that the perfect boat is the one that you are enjoying on the day. One of our industry’s legendary characters, John Haines Snr, once said that “we don’t make boats to take you to sea, we make them to bring you home safely!”

Boating has become quite specialised in many ways. There are dedicated ski, wakeboard, surf, dive, inshore, offshore, tournament, tender, inflatable, plastic and even collapsible boats for a multitude of applications. Yet the great majority of trailerable and moored boats are fibreglass and aluminium. The question is often asked by those new to boating, and in particular in the second-hand market, “What should I look out for when considering fibreglass vs aluminium boats?”

Material Innovation, Technology and Development

Aluminium and fibreglass manufacturing processes were mostly introduced to the recreational and commercial boating markets in the post-WW2 era, when these marvellous materials were shaped into boats. Most previous boats were made from planked or plywood timber with steel or even concrete alternatives.

Both fibreglass and aluminium are tremendous materials for boatbuilding. They can be formed, rolled, pressed or moulded to create hydrodynamically improved hull shapes to suit the purpose. Simply put, aluminium is lighter than the equivalent strength in fibreglass, so the design must have either a wider beam, more stabilising strakes and chines, a shallower V or deadrise, or introduced ballast – and/or a combination of each. The only other option would be to use thicker-section alloys, but there are limits to practical rolling and forming alloys. Lighter-weight hulls actually have some advantages, particularly in trailer boats.

The Strengths of Aluminium

Aluminium is a strong metallic material, but due to this, it doesn’t absorb the pounding surface and wave action, as does the more flexible fibreglass. From a human perspective, it can be damned cold in winter and hot in summer. Yet its lighter weight and immense strength lead to lower towing weight and horsepower requirements, plus enormous inherent strength. This makes them ideal for trailerable fishing and diving and very attractive for high-wear commercial applications.

There are several grades of aluminium and two major processes in manufacture. The most common are the “pressed” alloy boats, most commonly in grades up to 3mm thick but often down to 1.2mm for lightweight car toppers. Most people commonly refer to these as “tinnies,” and the process is most common in hulls up to around 6.5 metres.

Plate Aluminium

Stepping up a grade in aluminium are the “plate” aluminium boats. Most common plate alloy trailer boat hulls will often have 3 or 4mm side plates, but their bottom thicknesses will vary from 4, 5 or even up to 8mm. Plate alloy hulls are common in trailer boats from around 4.5 to 7.5 metres, but then the sky is the limit in larger craft, both recreational and commercial.

The Benefits of Fibreglass

On the other hand, fibreglass is naturally heavier than aluminium, and in my opinion, there’s no substitute for weight on the water to soften the ride. Fibreglass boats are moulded into intricate shapes with few limitations, broadening the spectrum of design. For example, ski and wake boats have entirely different premium design criteria than offshore fishing hulls.

It’s easy to change the weight and strength of a fibreglass hull simply by adding more glass and resin or by including many of the latest reinforcing materials and even injection moulding processes. However, fibreglass moulding is expensive and more restrictive to change than alloy.

What To Look For When Buying an Aluminium Boat

Marine-grade aluminium was a Godsend to marine manufacturers, but it does have its problems. Thankfully, most are quite easy to avoid and identify. The most common problems in aluminium hulls are split welds, fatigue, and what is commonly termed “electrolysis.”

Split Welds

Split welds are a major cause of concern. They are most common in lighter-weight pressed alloy hulls where the physical thickness of the material minimises impact resistance, weld and penetration, rendering them more prone to fatigue where a weakness is formed due to flex.

Fatigue

Fatigue is formed on stress points, sometimes during the rolling process, but more commonly with inappropriately manufactured items that can either be too rigid or improperly designed or gusseted, allowing movement in the sheet or weld that will eventually split. Splits can be very difficult to identify in their infancy, but one thing is certain – they never get any smaller! Sometimes, it’s worth filling a leaking hull with water to identify the source of a problem, but take great care as the added weight may overload the trailer, causing flow-on problems.

The good news is that a split or punctured hull can usually be welded using qualified and experienced MIG or TIG welding processes. Most welded repairs are quite easily identified unless they have been ground back or filled to the original surface level, and/or painted over with matching colour.

Electrolysis

“Electrolysis” has actually become a generic term for what is more accurately “Galvanic” or “Stray Current” Corrosion. By definition, electrolysis is a chemical change in a solution or electrolyte caused by an electric current. Aluminium is not a solution or electrolyte, and hence, the term is incorrect.

Galvanic Corrosion

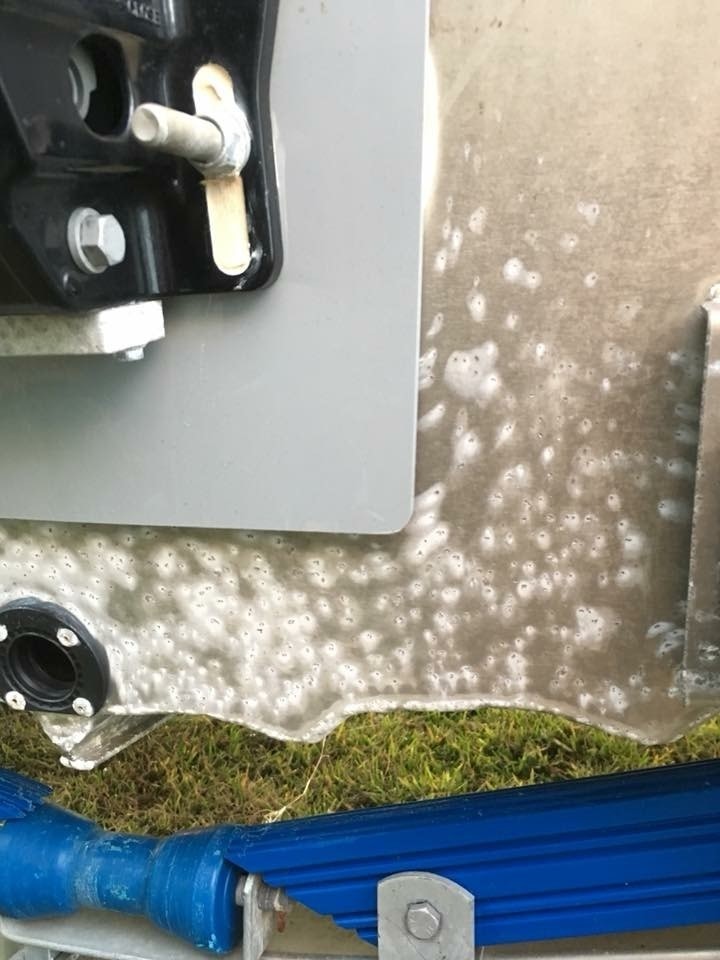

“Galvanic Corrosion” is the correct term and is commonplace in aluminium boats. It may be identified by blistering paint with chalky corrosion underneath. If unpainted, galvanic corrosion generally shows as lumpy surfaces similar to rust, but mostly soft and chalky. Depending on the level of corrosion, electrolysis may be simply a treatable surface issue, but if left unchecked, it may progress to turning an alloy boat virtually into unrepairable Swiss cheese. The degradation of the whole chemical structure of the alloy can corrode to a level where welding repair is impossible.

Galvanic corrosion occurs when two dissimilar metals, like aluminium and bronze, are in close proximity or contact, often in an electrolyte like seawater. This sets up an electrochemical reaction, essentially creating a battery. The more reactive metal (the anode) sacrifices its electrons to the less reactive metal (the cathode), leading to corrosion and degradation of the anode. In this case, the aluminium would corrode.

To minimise galvanic corrosion, it is imperative to keep all dissimilar metals away from contact. Essential fittings such as rod holders and bow rails would ideally be aluminium, but care must be taken with fastening nuts, bolts and screws, even stainless steel. Even aluminium pop rivets often have steel cores that corrode! There are a number of anti-corrosive jointing compounds to minimise reactivity in fastenings – ie Duralac, Sikaflex 291, TufGel, neutral cure silicone, Parafix polyurethane, etc

Many people don’t realise that there are acidic and non-acidic silicone sealants. Keep acidic sealants well away from aluminium. Paints often have high metal contents that will cause corrosion; similarly, the glues we use for carpets and liners must be compatible.

A very good friend and very experienced aluminium fabricator and repairer, Lawrence Moore from Triple J Welding in Melbourne, once told me that one of the worst things you can do to an alloy boat is to have a soggy material constantly in contact with the plate. Even a salty, wet newspaper can cause a catastrophe!

Some of aluminium’s worst enemies are lead sinkers lying in a corner or bilge undetected. These can corrode through a hull in no time! Another common mistake is having incompatible buoyancy foam in contact with a hull. Some foams are corrosive and retain salt water with little oxygen or a method to evaporate. The residual salt is also corrosive.

Electrolytic or Stray Current Corrosion

“Electrolytic or Stray Current Corrosion” is corrosion caused by stray (leaking) current from an electrical circuit in contact or proximity to the hull. The identification and result are virtually the same as galvanic corrosion.”

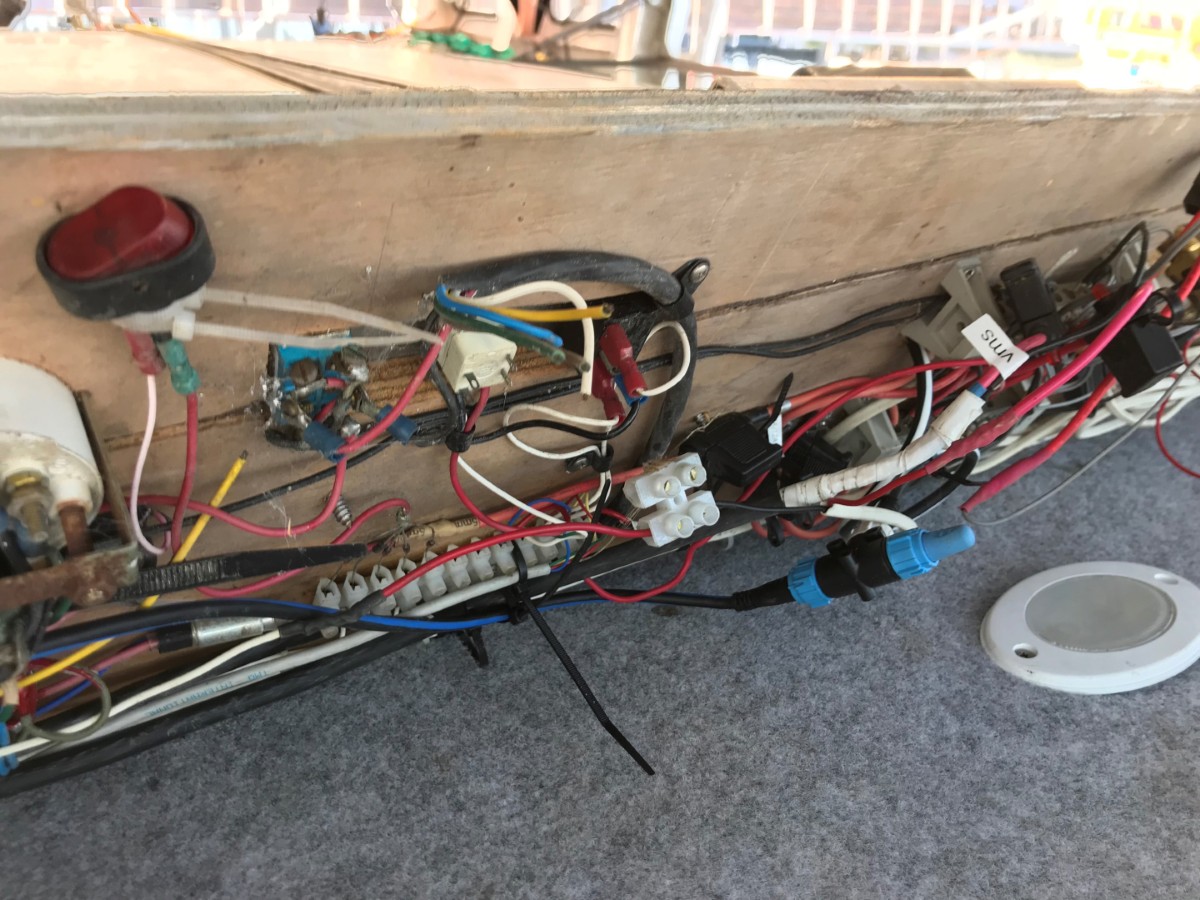

You may be shocked at just how little current can cause damage to a hull. Be sure that all of your electrical circuits and fittings are well insulated. In a moored scenario, bronze and stainless steel propellers can send out current through the water, causing stray current corrosion to neighbouring boats.

There are many more types of corrosion; however, galvanic and electrolytic corrosion are the major problems in most aluminium hulls.

Sacrificial Anodes

An anode is a positively charged electrode that attracts negatively charged electrons or anions. Sacrificial anodes are made from a metal alloy that’s more reactive than the structure’s metal. When connected, the anode corrodes instead of the structure, protecting it from damage. This process consumes the anode material, hence the term “sacrificial.”

In layman’s terms, anodes attract the corrosive charge rather than the hull or engine/drive component. Anodes are fitted to all marine engines, plus the rudders, shafts and drive units of moored boats. It is important to inspect the condition of the anodes on a marine engine prior to purchase. Don’t be afraid if it has corroded; it means it’s doing its job!

What To Look For When Buying a Fibreglass Boat

Fibreglass is a wonderful boatbuilding material. If manufactured and treated correctly, it has an indefinite lifespan. As fibreglass cures with time, it can get even stronger with age. Hence, if built appropriately for the design, a fibreglass boat should virtually live forever!

Fibreglass has an element of flex and hence more lenient impact absorbency than hard aluminium, generally making the medium softer and more comfortable on the water. It doesn’t have the harsh climatic hot and cold extremes of alloy, and can be moulded into more compound shapes to improve the hydrodynamics.

The actual weight and thickness of fibreglass can vary considerably depending on the manufacturer. Some are built with less fibreglass for low towing weight or performance, and others are built heavy for tougher offshore or commercial applications. Ben Toseland from Bass Strait Boats always reminds me that every hull has an individual, premium performance weight, matching the desired strength-to-weight ratio for the intended purpose. For example, a dedicated ocean-going game fisher will have higher demands than a weekend pleasure boat or a racing hull.

Fibreglass construction can also be quite varied with differing laminate thicknesses and types such as chopped strand and double bias cloths, carbon and even basalt fibres, and a wide range of synthetic coring and construction materials. Even the resin itself varies considerably in application, including polyester, vinyl ester, and epoxy, all with differing properties, including price, mechanical strength, chemical resistance, adhesion and moisture resistance.

However, there are a number of factors to consider when looking to purchase a second-hand fibreglass rig. Unless a hull has suffered some damage such as stress, impact or simply sun fade, it is generally the infrastructure and reinforcing that can let you down.

Timber or Synthetic Reinforcing For Fibreglass Constructions

Fibreglass hulls (often known as GRP or FRP – glass or fibre reinforced plastic) were traditionally built with timber stringers, superstructure, and transom sheets, and this is still entirely acceptable provided the type of timber is of suitable quality and that it is not only 100% sealed from moisture ingress during manufacture, but remains that way.

High-quality manufacturers often use hardwoods or moisture-resistant rainforest timbers with fine grain and no knots for the subfloor structures. These structures need to be totally encased in fibreglass to prevent moisture. Such moisture can be from an unsealed bilge, leak, or even condensation in unvented compartments, particularly those used for buoyancy. More commonly, water ingress is caused by insufficient or dilapidated sealing compounds where bolts, screws and fittings break the hull’s integrity.

In recent times, laminated plywood has virtually eliminated continuous natural timber. Plywood has always been used in fibreglass transoms where great strength is required to support outboard engines. A properly built timber transom will have thick fibreglass inner and outer skins and a series of strong plywood sheets, all laminated (or similar adhesions, such as marine epoxy) together to achieve the desired specification and then fully sealed.

As in any field, there have always been premium manufacturers and some with lesser standards who often take shortcuts. Some will use lesser quality materials and perhaps less quantity as well to produce a variance in standards that is not always reflected in the price. The external surface can be visually the same to an untrained eye.

There are various grades of plywood that vary enormously in price. For boatbuilding, we should only use those with a marine bonding system, and even “marine ply” comes in various types of timber veneer. Unscrupulous manufacturers have committed some enormous frauds over the years. I even recall one supposed “premium” manufacturer replacing marine plywood with cheap Masonite, mostly with dire consequences after the warranty expired!

Nowadays, it is rare to find a manufacturer that hasn’t replaced timber with synthetic construction and reinforcements, mostly resulting in even stronger and somewhat lighter strength and extended longevity. However, some constructions have shown some extent of delamination, which is usually only detected by a professional.

Common Issues with Fibreglass Boats

Over the course of many years, even the best-built boats can develop problems. Remember, many fibreglass boats have been in production for over 60 years! The most obvious are soft floors, stringers and transoms. The best way to check for such problems is actually physically by using your senses.

Visually check for damage, particularly in common stress points such as the strakes and chines and in the corners of the transom. If there are weaknesses, the external surface (generally gel coat) will most often show signs of cracking. Fine, hairline cracking along longitudinals such as chines and strakes, as well as small areas of “crows feet” around edges are nowhere near as bad as any east-west cracking across the hull. This east-west cracking can be indicative of a “broken hull” where the fibreglass has flexed and broken around an internal wear point such as a bulkhead or weakened internal beams and cross members.

Patching and Bad Repairs

Look out for areas of patching and bad repairs, particularly those that may indicate impact, or often wear points from badly fitting or inappropriate trailers. I have often seen cabin structures split, or broken across the dashboard, internal damage from leaking windows, hatches and anchor wells and many other “soft spots” where there has been impact or water ingress.

Floors and Transoms

The floors and transoms are major areas of concern. The transoms often had multiple layers of plywood structural reinforcing, and instead of being moulded, the floors were built from marine or construction ply (with marine bonding between the laminates) and sealed with fibreglass to often differing levels of professionalism. Water ingress causes rot in these areas.

Water Meters – Should You Use them?

Professional testing operators often use water meters to indicate moisture levels, but to be honest, I don’t trust many of them. Personally, I don’t believe there is any substitute for a good physical inspection, where you march heavily around on the floor, or lean heavily on the tilted engine, looking for any movement of soft spots. You can also tap all of these areas with a hammer or such, listening for delamination and soft spots; however, that is more for a well-trained ear.

Hulls and transoms can be rebuilt, but it’s a big, messy, and expensive job that is best left to experts.

Just a little note on such rebuilds. Many older fibreglass boats are being rebuilt as described, transoms lengthened, or pods fitted in the “Old School” fad. Be very wary of this as it’s often difficult to assess the quality of workmanship properly, let alone the engineering stresses and quality of ride. Most insurance companies will ask if the hull has been modified and by whom. Often, even though they have been inspected and taken the insurance premiums, they will use this as a get-out clause in the case of any accidental damage. Yes – it has happened to me, and all my work was done by a qualified boatbuilder and shipwright!

All Hull Inspections Should Include

- Construction material

- Main floor/deck

- Side and bow decks

- Seating and trimming

- Fuel tanks, fillers, filters, and hoses

- Corrosion or electrolysis

- Windscreen and wipers

- Bimini and clears

- Sea Cocks, skin fittings, and hull penetrations

- Doors, windows, lockers, and hatches

- Rub strip / rails

- Hull condition above waterline

- Hull condition below waterline

- Swim platform & ladder

- Transom condition

- Antifoul, anodes

- Impact damage, stress, wear, delamination, rot, and osmosis. Electrolysis, corrosion, and rust. Anti-fouling, fade, crow’s feet, stress cracks, and fracture.

- Registration and ownership details

- Hull identification number and manufacturer’s ID plate

- Safety gear

Getting a Quote Before You Buy

Credit One makes boat finance simple! No fuss, just great rates and fast approvals. Fill out our easy online loan application to get started.

Not quite ready to apply? Try our loan calculator to estimate your repayments and explore your options.

And if you’re still in shopping mode, check out the great selection available at Only Boats! You’ll find deals on all kinds of boats for sale, including aluminium boats and fibreglass boats for sale. You can also check out our complete used boat buying guide there for more detailed information.

Wayne Park

Automotive Content Editor

Wayne is a Senior BDM with the Credit One Group. He specializes in the leisure space and has over 12 years’ experience dealing with both the Caravan and Marine market. He has been awarded by Caravanning Associations for his continued commitment to the industry and is widely respected by industry members. As a BDM and working for Credit One he loves nothing more than helping people achieve a lifestyle choice to start their journey and enjoy the great outdoors, whatever that dream looks like.

Get a Quick Quote

You don't need to make a decision right away. Find out what your loan will cost before you commit to it. Getting a quote is easy, won't hurt your credit score, and only takes a few moments - secure yours today.